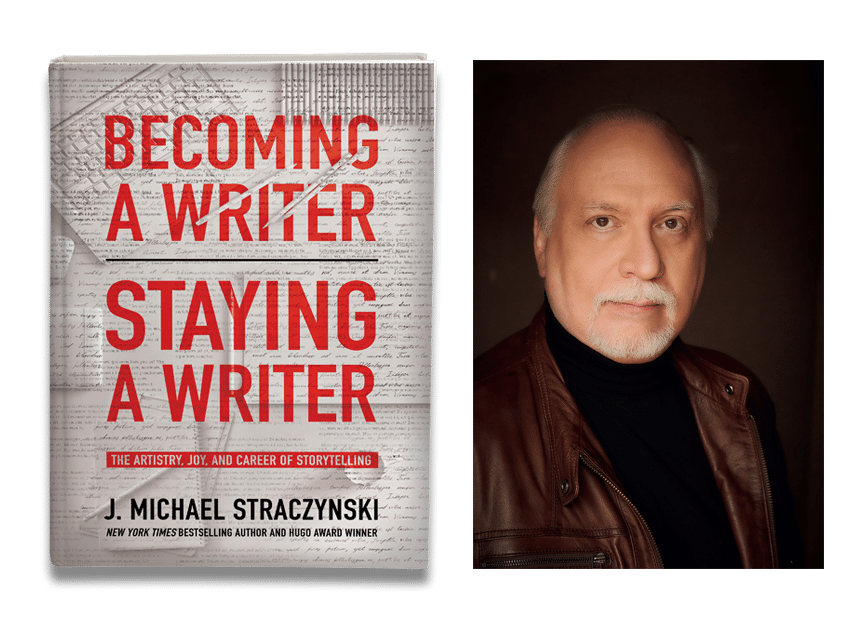

If you’re like us, you’re currently rewatching Babylon 5 now that it’s streaming on HBO Max (finally!). And, since you’re like us, you also know that it, along with a host of other books, shows, and films, were created and written by the award-winning J. Michael Straczynski. The Smart Pop team is thrilled to share an excerpt from Straczynski’s new book: Becoming a Writer, Staying a Writer (coming in June but available for preorder now).

If you put a bunch of writers in a room and one of them starts talking about how the people in their head have always felt more real and substantive than anyone else they know, and how the work is constantly pulling them against their will into all the deep places where stories abide, the rest will nod their heads in recognition. Yeah, that’s how it is for me, too, they will say, like members of a twelve-step program admitting to a unique and unshakeable addiction that they can’t share with others because a) they wouldn’t understand and b) most of us are still figuring out that whole making-direct-eye-contact thing with non-writers.

So, if you, gentle reader, also found yourself nodding with painful familiarity as you made your way through the preceding pages . . . congratulations—you’ve found the right book.

One doesn’t have to be a socially maladroit loner with a penchant for daydreaming and a roster of friends who exist only in one’s head to be a writer, but to be honest, that does describe a lot of us. But it’s also possible to be all those things and not be a writer. So what makes the difference? Whence the Rubicon?

I think it starts with the belief that we have something to say that may actually be worth listening to. As a kid who was always being told to shut up, written off as a dead-ender by family and teachers alike, I was determined to show the doubters that I had an important story to tell, one that would change the world. That obsession is sometimes necessary to carry us through periods of self-doubt, but it can also result in the Great American Novel complex that paralyzes so many writers. Sure enough, every time I tried to make the work sound important, it came out the other side pompous, pretentious, portentous, self-indulgent, and stuffy. Desperate for acceptance and applause, I kept bending the writing impulse to the result rather than embracing the process, more focused on how I wanted the world to perceive the work than on the quality of the work itself.

It took me years to realize that my priorities were upside down.

It’s not about writing something important, it’s about writing something true, and truth rarely shouts its importance. It tends to speak very softly, and only if it’s sure you’re listening.

Early atomic bomb tests produced massive explosions. But what made those explosions happen was a small amount of explosives placed with care at the center of the device. This triggered a chain reaction that ignited the fissionable material, which then spiraled into a massive detonation. Take away that tiny, painfully precise explosion at the center, the big event would never happen. And as I made my way into television writing, I began to realize that truth in storytelling works much the same way. Instead of trying to yell out a big truth, it’s sometimes better to put a small but relatable truth at the center of what you’re creating in the hope of igniting the fissionable material of the human heart, thereby triggering an explosion of empathy, self-reflection, and understanding.

The smaller the truth, the more universal it is, because we all have experience with small but potent truths; by contrast, the bigger and grander the statement, the less universally applicable it can become. People rarely talk in profundities; most of the time they speak in small but deeply personal truths that are less about the Meaning of Life than what it felt like when the last of their grandparents passed away.

This understanding crystallized into something practicable during my tenure as the executive story editor on a reboot of The Twilight Zone. I was having dinner with friend and mentor Harlan Ellison (from whose tutelage the title of this volume is derived), and hit him with a question about a script I was writing.

“The main character’s wife died in an accident several years earlier,” I said, “and he’s still not over the grief. He’s tormented by the fact that the last time they talked, the conversation turned into an argument, so I’m looking for something interesting they can argue about. Maybe he thinks she’s spending too much money, or there’s a political argument, or they’re behind on rent, or one of them suspects the other is having an affair . . . I’ve tried a bunch of different subjects but none of them seem to work, so I thought you might have a suggestion.”

“Those are certainly all big arguments,” Harlan said.

“Yeah,” I said, failing to perceive the trap that was being set before me. “I think it needs to be something substantive.”

“And that’s exactly why it’s not working,” he said. “Arguments like the ones you described happen all the time, and they’re just standard TeeVee stuff. Yeah, he’d feel bad about arguing with her before she died, but he wouldn’t necessarily regret it on a very personal basis because rent happens, bills happen. You know what we regret? We regret all the really stupid things we’ve done, the stuff that comes out of nowhere to haunt us while we’re sitting at a stoplight waiting for the green.

“So, instead of arguing about rent, how about this: You know those jars of cherry or plum preserves you get at breakfast? He always called them jams but to be cute and funny she called them jellies instead, so every morning for the last thirty years he’d say, ‘Pass the jam, dear,’ and she’d say, ‘Here’s the jelly, dear.’ Then one day he was in a bad mood—maybe he didn’t get a good night’s sleep or there’s something else bothering him—and when she says, ‘Here’s the jelly, dear,’ he just goes off on her, saying that after thirty freaking years it’s not funny, it’s never been funny, and when he asks for the goddamned jam just give him the goddamned jam and stop giving him crap about it.

“They finish breakfast in that stony, post-argument silence, and he knows he overreacted but he has to get to work so he figures he’ll apologize later. But she gets killed in an accident that afternoon and later never happens. So it’s not just that they argued, it’s that it was a stupid argument because he was being an ass, and unfair, and petty, and he’d give anything to have those five minutes back so he could make it right.”

Not rent. Not politics. Not affairs. Because that’s just stuff people argue about all the time and sometimes it’s nobody’s fault. Jams and jellies. Because on a core emotional level we understand how deeply we’d regret having an argument that petty, stupid, and unnecessary with a loved one on the last day of their life.

That was the afternoon the words If You Want to Go Big, Go Small were forever etched behind my eyes.

Becoming a Writer, Staying a Writer copyright © 2021 by Synthetic Worlds, Ltd.