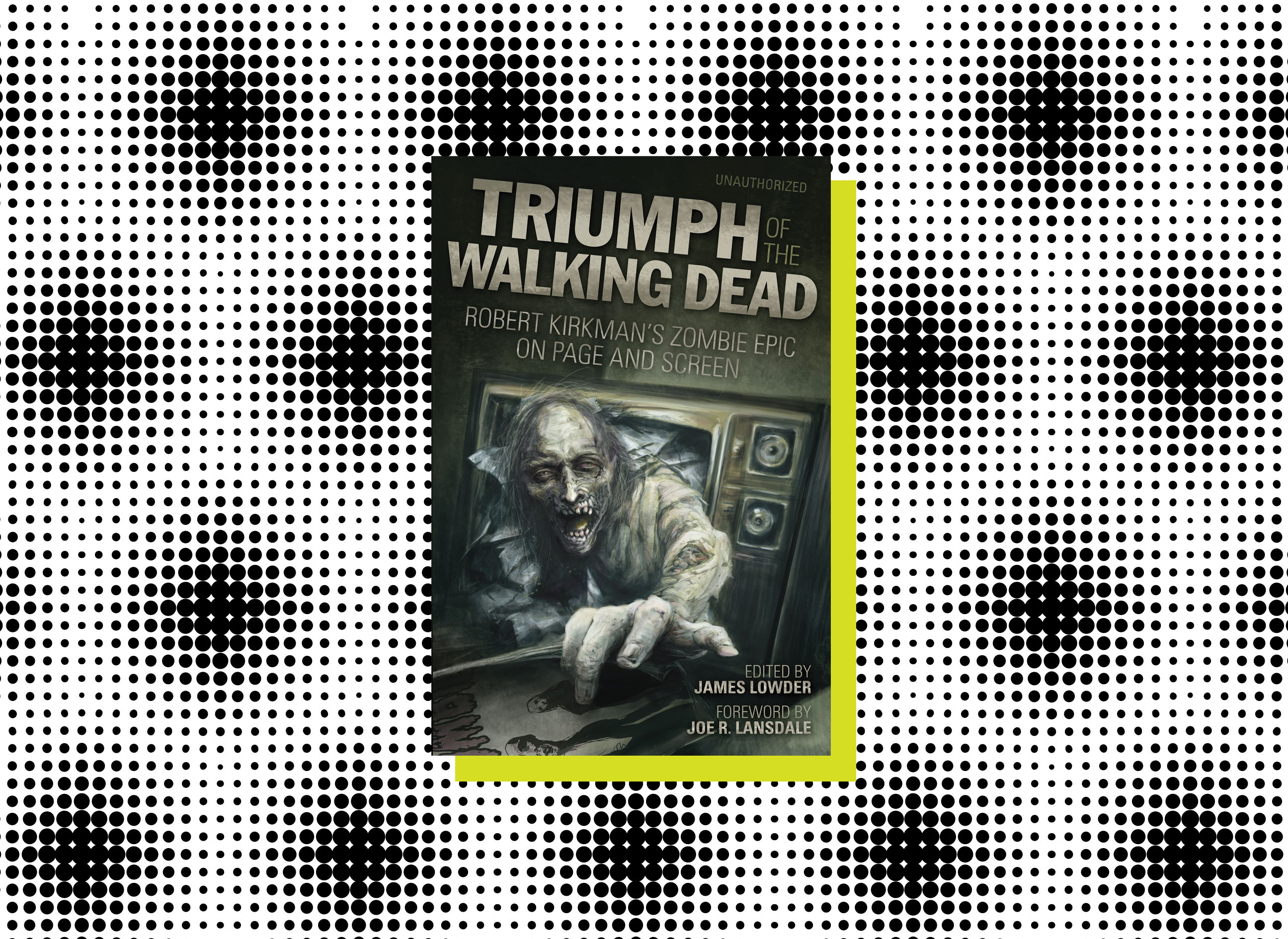

In the Smart Pop Classics series, we share greatest hits from our throwback essay collections. This week, Brenden Riley explores the complicated nature of personhood in his essay “Zombie People” from Triumph of The Walking Dead: Robert Kirkman’s Zombie Epic on Page and Screen.

She’s not your mother anymore.”

—Ed, Shaun of the Dead“I don’t want to be walkin’ around like that.”

—Roger, Dawn of the Dead“Keep your funeral, dear. Timmy and I are going zombie.”

—Helen, Fido

Zombie stories scare us in many ways, triggering our primal fear of being eaten alive, our instinctive horror of corpses, and even our unconscious worry about the collapse of civilization. They spur our imagination, helping us contemplate how we would handle ourselves during a large-scale, life-threatening crisis. Most zombie tales also expose a fascinating paradox about the living dead. On one hand, the human characters believe reanimated corpses are no longer the people they once were. Nearly every zombie text features a conversation like the one from Shaun of the Dead (2004) in which Ed persuades Shawn that the zombie Barbara is no longer her former self. On the other hand, many stories also include a moment in which someone who has been bitten begs to be shot, as Roger does from his deathbed in Dawn of the Dead (1978). This paradox about the relationship between a person and their zombie corpse threads through the Walking Dead comic. However, because the comic has had such a long run, it takes this contradictory perspective to new extremes, challenging how we understand the relationship between minds and bodies. The comic complicates what it means to be a person and draws attention to the situated nature of our identities.

That’s Not Your Mother . . . Or Is It?

Most zombie stories assert early and often that zombies are not the people they were when they were alive. The Walking Dead made this perspective abundantly clear very early on. Throughout the initial story arc, “Days Gone Bye,” human survivors discussed zombies only in terms of practicalities— how to kill them, how to avoid them, how they sense the world, and so on. Aside from a little initial trauma, the survivors showed no compunction about killing zombies and no concern that the zombies might be people. In “Miles Behind Us,” Rick nearly came to blows with Hershel after learning that the farmer’s zombified neighbors and family occupied the barn:

Rick: We’re putting them out of their misery, and keeping them from killing us! Those things aren’t human. They’re undead monsters [. . .] I don’t think I could live without my son . . . But you’ve got to listen to me, Hershel. That thing in the barn . . . it’s not your son [. . .]

Hershel: We don’t know a goddamn thing about them. We don’t know what they’re thinking—what they’re feeling [. . .] For all we know these things could wake up tomorrow, heal up, and be completely normal again! We just don’t know! You could have been murdering all those people you “put out of their misery.”

The narrative up to this point provided no reason to think the zombies possess feelings or thoughts, and the events that follow bear out Rick’s contention that keeping zombies around—even locked up—is dangerous: the zombies in Hershel’s barn escape a few pages later, as do the zombies left alive in the unused parts of the prison. But even as Rick claimed that protecting the zombies was unreasonable, he revealed his own doubt when he used the phrase “out of their misery.” Despite his uncompromising stance toward killing the zombies, he and the other survivors also recognized that the zombies might be suffering, cursed to walk the earth, always hungry.

The comic established this dynamic early on. In issue one, Rick found a zombie in the weeds next to the road. It had decayed too much to move, so it merely gasped up at Rick as he stood over it. The look on his face might have been horror or disgust, but the tear that rolled down his cheek suggested that Rick felt empathy for the pathetic creature. The end of the issue confirmed this empathy when Rick stopped on his way out of town to shoot the zombie, a moment mirrored in the first episode of the television series. Once again, he cried. The idea of empathy for the zombies appeared again in the third major story arc, “Safety Behind Bars.” When Rick discovered that everyone reanimates, whether they died from a bite or not, he took a long journey to find zombie Shane. After he dug Shane up, Rick said, “When I realized you might be at the bottom of that hole, alive—or whatever—I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I couldn’t sleep—knowing you were down there. Would you have left me? [. . .] Could you have lived with yourself? Not me. I had to set things right.” As with the zombie by the road, the fact that Rick went out of his way to put the zombie down undermines his outspoken claim that the zombies are no longer the people they once were.

More significantly, The Walking Dead has thus far avoided that other clichéd zombie trope: the plea to be kept from rising again. Unlike Dawn of the Dead (1978) or its myriad imitators, the comic implies that some people may prefer the zombie life to no life at all. Early in the series, Jim got bitten during a scuffle with some roaming zombies. As he sickened, he asked to be left alone in the woods instead of tended to (and killed) by the group, saying, “L-Leave me. When I come back . . . maybe I’ll find—find my family . . . Maybe they c-came back, too. Maybe we can be together again.” Despite the carnage he’d seen, Jim held out hope that being a zombie would be better than being dead. Doctor Stevens made a similar choice in the sequence “This Sorrowful Life” after being bitten. “I’m not dying . . . Think of it scientifically . . . I’m just . . . evolving . . . into a different . . . worse life-form. I’ll still exist . . . in some way.” Like Jim, Stevens preferred zombie life to total death. Despite claims to the contrary, the survivors continued to see the zombies, at least partly, as the people they used to be.

What Is a Person?

Science fiction has long struggled to identify what separates people from the rest of the biosphere. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, often cited as one of the first science-fiction works, turns on this very question: If we could make a creature that seemed to be a person, would that creature be a person? That same question has reverberated since, in works such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). When we develop the tools to create artificially intelligent entities, we will have to decide whether those creatures should have equal rights and justice under our legal system. We will need to revisit our definitions of what it means to be alive, to be sentient, and we will need to answer those individuals when they call for access to resources and opportunities to make lives of their own.

Philosophers have also considered the question of identity from a variety of different perspectives. John Locke famously claimed that consciousness defines personhood, suggesting a distinction between the mind and the body. For Locke, if two individuals were to swap minds, Freaky Friday–style, those minds would retain their identities in new bodies. This perspective is updated and reinforced by John Searle, whose “Chinese room” problem also differentiates between the ability to imitate consciousness and the being at the center of actual consciousness. By contrast, other philosophers find the mind inseparable from the physical brain, and work to understand how the disembodied sense of consciousness can emerge from the impulses of neurons. In I Am a Strange Loop, modern philosopher Douglas Hofstadter argues for a much hazier line between person and non-person, describing complexity of thought as a sliding scale on which he is unwilling to demarcate a border. Looking at the abstruse landscape of philosophy contemplating this mind/body problem, René Descartes’ famous dictum, “I think, therefore I am,” seems almost like an abdication from the debate.

At the same time that science-fiction writers and philosophers contemplate minds of all kinds, our political and social sciences seethe with debate over the real-world definition of personhood. It wasn’t so long ago that upstanding members of society argued vigorously about whether certain human beings were, in fact, people. The rhetoric that classified persons of other races, faiths, or geographic heritage as subhuman served the economic and social needs of the expanding European states and America. By dehumanizing people kidnapped from Africa, for instance, Americans could rationalize treating those people like cattle (as in the Dred Scott decision, in which the U.S. Supreme Court found that slaves had no legal rights because they were property). The ongoing effects of such institutionalized racism are still visible in our culture’s economic and social disparities today.

More recently, debate about personhood has focused on the beginning and end of life. At the beginning, opponents struggle to define a person in the context of a human embryo. Many pro-life advocates argue that the moment of conception should be considered the beginning of life, and that abortion should, therefore, be illegal. But pro-choice factions argue that the embryo meets none of the conditions we normally associate with life: it cannot survive outside the womb and has no clear markers like a heartbeat or brain activity. The legal system has been no help, drawing a relatively arbitrary line distinguishing “embryo” from “unborn child.” Regardless of where we stand, the debate turns on how we understand personhood.

A similar struggle emerges over questions about when we stop being a person. Leaving aside thoughts on the afterlife, most everyone agrees that our personhood ends when we die. But we struggle more with changes to our state of mind. America considered this question on a national stage during the legal struggle around Terry Schiavo. In March 2005, the parents of Schiavo, a woman who had been in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) since 1990, gained national attention due to their court battle to prevent Schiavo’s husband from removing her feeding tube, a process he had begun seven years earlier. The national attention amplified as members of the U.S. Congress and President Bush sided with Schiavo’s parents. As the court battle progressed, debate raged about the status of people in persistent vegetative states. Some claimed PVS victims were conscious and trying to communicate by means of their damaged bodies; others argued that such communication was pareidolia, a phenomenon by which we recognize patterns in otherwise random stimuli. As with abortion, our perception of the Schiavo affair depends on when we believe someone stops being a person—if her body is alive and her brain has ceased all its higher functions, is she still alive? We can’t help but wonder when she stopped being the person her family knew her to be.

We have similar concerns about individuals with less severe brain injuries. It is unclear whether significant changes to the brain via injury, disease, or medication change the person, especially if the person’s behavior varies significantly because of those changes. When people with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or similar degenerative diseases experience dementia, they often act and speak differently. While no one would suggest that senile men and women are not people, many would agree that they are no longer the people they once were. The same goes for individuals with significant brain injuries. It is difficult to argue that a person with little or no memory, like Lenny in the Christopher Nolan film Memento (2000), is still the same person he was before his accident. People with dementia or severe brain injuries inhabit the same bodies but seem to have different minds.

On a more mundane level, the question of personhood demands a complicated answer even for people without such obvious trauma. Recovering alcoholics seem to be different people once they stop drinking. Individuals with lifelong chronic depression undergo major personality changes when they begin receiving medication to balance their brain chemistry. Both types of people see the world differently, act differently, even make and build relationships differently. We can even consider the way a person changes as he or she matures in light of this question. Few of us consider ourselves, fundamentally, to be the same person we were as a child: our outlook on the world has changed, perhaps in no lesser way than that of someone who is on a new medication or recovering from an addiction.

The Walking Dead tackles these questions throughout its long run, using the dramatic backdrop of the zombie apocalypse to bring matters of personhood and identity into stark relief. It challenges us to rethink how we understand ourselves and others.

Complicated People

Throughout The Walking Dead, surviving humans work very hard to define themselves in ways that maintain their sense of humanity, even at the cost of dehumanizing others. Rick and many of the other survivors tell themselves that zombies are no longer people, as if intentionally avoiding their suspicions that the undead are more complicated than that. To be fair, the world of the comic demands such a perspective. Hershel’s pained pleas for his zombified son, Shawn, to “remember!” fell on necrotic ears, just as Tyreese’s cries did nothing to tame his daughter Julie after she turned at the prison in “Safety Behind Bars.” The unrelenting horror of being eaten by their loved ones pushed the survivors to pretend they have an uncompromising attitude toward the zombies.

At the same time, in moments of calm, some members of the group took a more nuanced view of the zombies. For instance, while he and Hershel plowed the prison yard for crops, Axel mused about the zombies:

I think about them all the time. Who they were—what they did before they died—all kinds of stuff [. . .] I wonder what it felt like when they died. I wonder what it was like to start turning into one of them—to come back. I wonder if it hurts. I bet it hurts real bad. That’s why they moan so much. You gotta ask yourselves these questions. (“The Heart’s Desire”)

During this conversation, which Hershel frowned on, Axel underscored the similarities between people and zombies. He read emotion in their actions and empathized with them. Sophia and Carl expressed similar thoughts a few pages earlier. When Carl asked Sophia why she felt sorry for the zombies, she said, “Because they look so sad. Don’t they look sad to you?” When the survivors are not in fight-or-flight mode, they have time to reflect on their close relationship to the zombies, which softens their hardened stance toward the walking dead.

Conversely, in times of trouble, the humans applied the same dehumanizing strategies to one another that they used to maintain the line between humans and zombies. This became most evident in the Woodbury story arc. Rick, Glenn, and Michonne discovered a neighboring community of survivors ruled by a madman called the Governor. While the narrative focused mostly on the Governor and his villainous henchmen, it also provided a clear sense that the people living in Woodbury did not realize the extent of the Governor’s horrific crimes. In fact, his political savvy allowed him to paint Rick and the other survivors in the prison as vicious enemies. Later, after he recovered from Michonne’s attack, the Governor gave a speech calling Rick’s group “ruthless, inhuman savages” and “monsters.” During the following attack, his people believed they were fighting for a just cause against murderers. While the comic clearly established the Governor as a madman, the speech mentioned above sounds familiar because Rick used it not too much earlier. After discovering that Martinez intended to lead the Woodbury group to the prison, Rick ran him down with the RV and throttled him as he lay on the ground. Shouting at the dying man, Rick used the same rhetoric: “You people are a poison—a plague worse than the dead! [. . .] You’re animals!” While strangling Martinez to death, Rick shouted, “Don’t you know what people are capable of?!”

This parallel language highlights the ease with which humans in the story twisted their own priorities to survive. At times, The Walking Dead blurs the line between human and inhuman, calling into question values by which the characters (and, vicariously, the audience) define humanity. This becomes all the more clear in the regular similarity between images of people and of zombies throughout the comic. For example, near the beginning of “The Heart’s Desire,” the humans battled a herd of zombies inside the prison fence. Adlard rendered eight humans and eight zombies in a grid of sixteen portraits, with each featuring varying amounts of chiaroscuro, explosions or wounds, and open, angry mouths. The mix of images created a graphic parallel between the zombies and the humans: at a quick glance, the two groups appear quite similar. The cover art of various editions of the comic also bears out this parallel. Most strikingly, the cover of the first The Walking Dead Compendium features a mirrored image with the humans on the top and zombie versions of the characters below.

At the same time, as the humans used language to keep themselves from seeing zombies as people and to see antagonistic survivors as less than people, the comic presents anomalies that prod the reader to doubt that the line between zombie and human is as clear as Rick’s group claims. Most striking are the zombies who were traveling with Michonne when she first arrived at the prison. She kept them in chains and had removed their lower jaws; they walked along behind her, apparently keeping other zombies at bay. When Otis asked about them, she said, “These two stopped trying to attack me a long time ago. My boyfriend and his best friend.” Up to that point in the comic, there had not been any other “tame” zombies. Later, in the story arc “The Best Defense,” we learned a bit more about zombie psychology from the Governor, who revealed that well-fed zombies are happier and less likely to attack. We also discovered that the Governor was keeping his zombified daughter chained up in his apartment. These developments complicate the notion that zombies are empty shells operating on the hunger instinct alone. Instead, they can be sated and even trained.

Finally, The Walking Dead seethes with the question that has haunted us as long as we’ve had civilizations: What happens to our humanity when we do inhumane things? Our first glimpse of the coming turbulence arose toward the end of “Days Gone Bye,” when Carl shot Shane to defend Rick. Clinging tightly to Rick, Carl sobbed, “It’s not the same as killing the dead ones, Daddy.” Rick held him close and answered, “It never should be, Son.” Rick’s answer serves as an anthem throughout the comic, providing a bearing when he lamented that he had drifted too far away from the man he believed himself to be. For example, after he killed Martinez in “This Sorrowful Life,” Rick worried that he had lost his moral center:

Killing him made me realize something—made me notice how much I’ve changed. I used to be a trained police officer—my job was to uphold the law. Now I feel more like a lawless savage—an animal. I killed a man today and I don’t even care [. . .] But it made me realize how detached I’ve become. I’d kill every single one of the people here if I thought it’d keep you safe [. . .] Does that make me evil?

The desensitizing effect of killing so many undead and the violence all around him shook Rick’s ideas about who he is. Despite his own sense that his actions were correct, Rick suggested that he had changed, and worried that he had violated the code he’d sworn to uphold when he became a police officer.

Inhumane Humans

Throughout the comic we see many instances of people whose actions in the wake of the zombie apocalypse fundamentally changed who they were. “Fear the Hunters” illustrates these changes particularly well, underlining the notion that one’s actions define one’s humanity, or lack thereof.

First, the group had to grapple with Ben, the boy who killed his brother for apparently no reason at all. Early in the series, the boys seemed relatively normal, but over the course of the first nine volumes, they lost both their parents and saw friends murdered. Violence was a part of their daily lives for as long as they could remember. While the readers got an early glimpse of Ben’s emerging madness when we saw him vivisecting a cat at the end of “What We Become,” his brother’s murder came as a shock to the survivors. Ben’s act fundamentally changed him in their eyes. They realized that he really didn’t grasp the difference between right and wrong; as Michonne put it, “He’s a boy who doesn’t understand murder.” But they also wrestled with what do to about him. Abraham summarized their dilemma:

If this kind of thing happened in the real world—before all this madness—he’d get what—twenty years of therapy? He’d be sent off to some kind of home for the rest of his life and even then they’d probably never fix him. That’s not an option here. None of us are therapists . . . none of us can help this boy. He’s simply a burden—a liability.

Therapy is a luxury in their world, and they don’t have the resources to handle a dangerous person among them. Like Thomas, the serial killer in “Safety Behind Bars,” the only solution seems to be to kill the murderer. Unlike the situation with Thomas, however, the adults in the group are hampered by their affection for Ben and are hesitant to kill a child.

The last panel on the page exploring this debate shows that Carl, another child who has grown up over the course of the comic, has no such hesitation—his determined scowl makes it quite clear that he understands what needs to be done. While the adults still wrestle with their allegiance to the “real world” they grew up in, Carl grasps the more vicious but necessary law of survival at work throughout the comic. Thus he kills Ben in the night before Ben can kill again. When Carl and his father later talk about it, Rick reiterates that, “When we do these things and we’re good people . . . they’re still bad things. You can never lose sight of that. If these things start becoming easy, that’s when it’s all over. That’s when we become bad people.” Rick, Carl, Abraham, and the others struggle daily to understand how the context of someone’s actions defines their humanity. Ben’s senseless and remorseless murder of his brother made him monstrous; Carl’s hesitant but moral killing keeps him sympathetic.

Then the group met Father Stokes, a priest whose own sense of self had been sorely tested since he locked himself in his church and left his congregation outside to die. When Rick and the other survivors met him, he was wracked with guilt over his inaction, and had not yet really had to defend himself against zombies or other people. After Dale disappeared, Rick confronted Father Stokes, who confessed his cowardice. Stokes sobbed, “I know what I did. I know what I deserve. Kill me. Please. I’ve suffered enough—I want you to do it.” Then he collapsed in a corner, weeping. Father Stokes’ actions highlight another kind of moral lapse: his failure to protect those around him.

Up to this point, the failure to act had not been a strong storyline in The Walking Dead. One could argue that Hershel the farmer suffered from this problem, as did some of the side characters in Woodbury who failed to intervene against the Governor, but these storylines were incidental to the main focus on the way murder and killing erode one’s humanity. By contrast, the Father Stokes storyline highlights how someone could become monstrous by failing to follow through with his ideals. When Stokes locked the doors to his church and left his congregation outside to die, he failed to uphold his principles. His dead parishioners haunted him, leading him to beg Rick to end his life. Father Stokes’ selfishness represents a different kind of inhumanity brought forth by crisis.

Finally, the suburban cannibals presented another inhuman perspective with which Rick and his friends grappled in “Fear the Hunters.” As the survivors mourned the deaths of Billy and Ben, Dale was captured by a cadre of hunters who preyed on passing groups. When Rick confronted them, they explained that cannibalism was their last recourse and that they had eaten not only people who happened by, but even their own children. The survivors overpowered the cannibals, then tortured them. As Rick described it later:

I can’t stop thinking about what we did to the hunters. I know it’s justifiable . . . but I see them when I close my eyes . . . Doing what we did, to living people . . . after taking their weapons . . . it haunts me. I see every bloody bit. Every broken bone. Every bashed in skull. They did what they did, but we mutilated those people. Made the others watch as we went through them . . . one by one.

Rick continued to be haunted by the actions he and others had taken to survive, but the things they were willing to do kept getting more vicious. Rick’s claim to be justified in torturing the cannibals stretches beyond the ethical framework he had clung to so far: even savage actions are acceptable in order to protect the group, but that savagery must be tempered by necessity, and the living must recognize it as “bad.” Torturing the hunters may have crossed that line.

The ethical and emotional trials facing the survivors in “Fear the Hunters” highlight the many ways times of crisis challenge the ideals on which we base our humanity. When Ben killed Billy, the group had to reconsider its approach to justice in order to weigh the responsibility of a child murderer against the safety of the group. The Father Stokes storyline introduced the idea that inaction could be just as immoral as action. And in torturing the hunters, Rick and the other survivors further undermined their own hold on civilization, killing not for self-defense, but for punishment as well.

We Are the Walking Dead

At the end of “The Heart’s Desire,” Rick stomped around the prison yard, yelling at the other survivors. He blamed himself for being naïve and shouted that they were becoming the very dead they’d sought to kill. He claimed that they would still try to know right from wrong, but that they would do whatever it took to survive. Then, in a bleak moment of despair, he raged, “We are the walking dead!”

The complicated nature of personhood in The Walking Dead undermined the black-and-white moral judgments Rick had been trying to make. Throughout the series, survivors contrast their humanity with the savagery of others, often finding the values they attached to being human challenged by the circumstances of their survival. When Tyreese objected that they “don’t want to become savages,” Rick replied, “We already are savages.” In doing whatever it took to survive, Rick and the others had fundamentally changed their own natures. But at the same time, Rick consistently returned to the idea of conscience as the key to maintaining one’s humanity, relying on his ability to recognize acts as “bad but necessary” to reassure himself that he was still a good person.

The violent circumstances facing characters in The Walking Dead force them to make choices that are far more extreme than anything most of us will ever experience. But just as Rick finds the values he holds most dear challenged by the difficult decisions he must make, so too must we struggle with challenges facing our own civilization. From the fractious line between technology and ethics to the give-and-take between individual liberty and collective need, the choices we make force us to weigh circumstances against values. In the darkest times, perhaps we’re not so different from Rick, in that the best we can do is to cling to the values we hold most dear, so that we can remain good people, even when we must do bad things.

Want more on the Walking Dead? Order your copy of Triumph of The Walking Dead.