In the Smart Pop Classics series, we share greatest hits from our throwback essay collections.

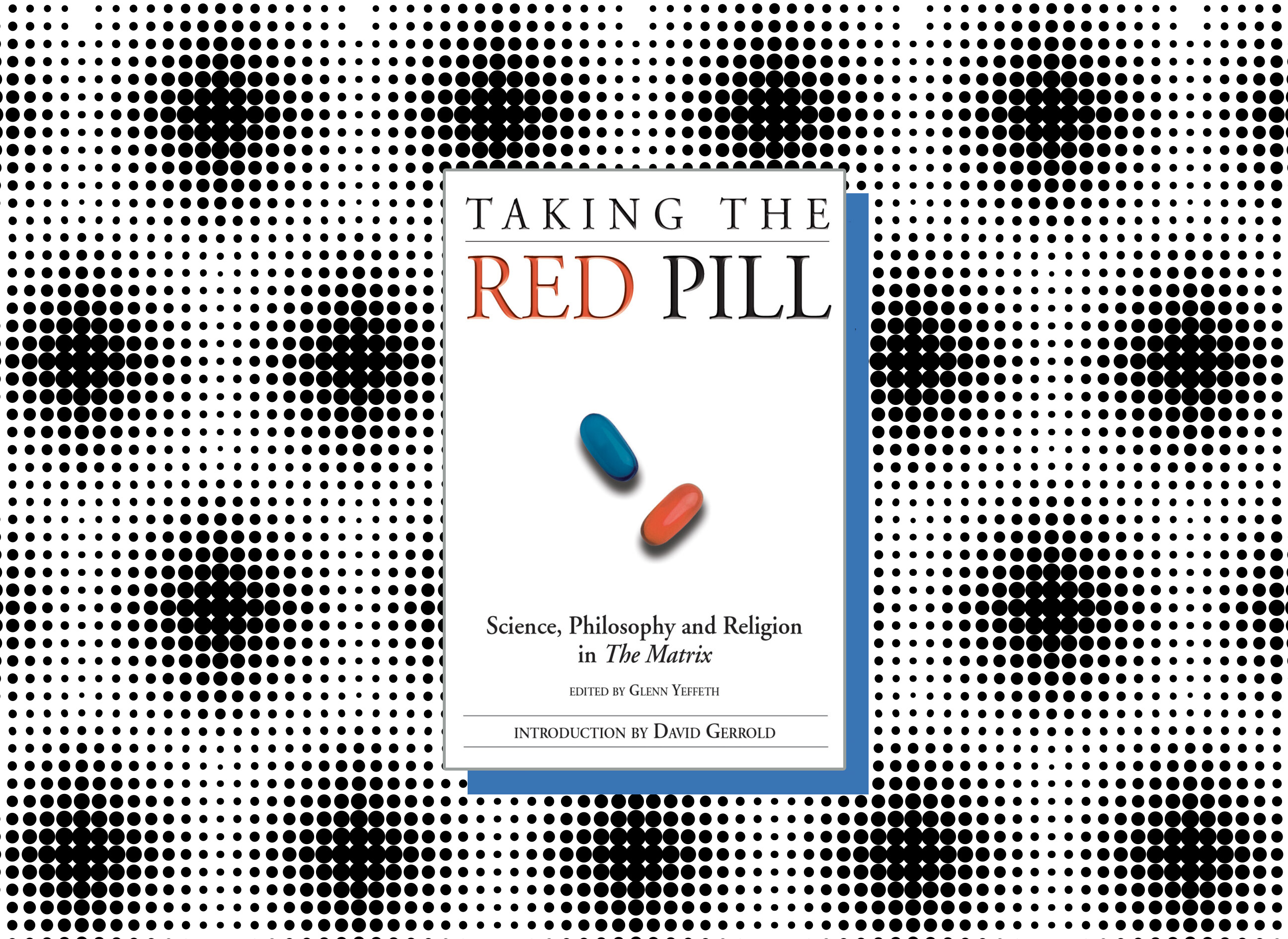

This week, media and cultural critic Read Mercer Schuchardt presents the definitive answer to the question “What is the Matrix?” in their piece from our very first Smart Pop book, Taking the Red Pill: Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix.

Parable

While the stated reason for the early release and accelerated postproduction process of The Matrix was to beat the marketing hype that surrounded The Phantom Menace, it is not without coincidence that The Matrix was released on the last Easter weekend of the dying twentieth century. It is a parable of the original Judeo-Christian worldview of entrapment in a world gone wrong, with no hope of survival or salvation short of something miraculous. The Matrix is a new testament for a new millennium, a religious parable of the second coming of mankind’s messiah in an age that needs salvation as desperately as any ever has.

Keanu Reeves plays Thomas Anderson, a computer programmer by day who spends his nights in the alternative reality of the Internet, where he goes by the name Neo, spending his time among hackers and phreaks who have come to rely on his expertise. Symbolically, Reeves’s character plays that of both new convert and Christ in the film and is on the receiving end of some of the world’s most ancient wisdom wrapped in some of the best modern technological analogies. “You are a slave” and “We are born into bondage” are the two sentences Morpheus speaks to Neo that reveal the analogy to the Judeo-Christian understanding of slavery as sin. Like the biblical understanding, our technoslavery is a bondage of mankind’s own making, a product of our own free will, as evidenced by Agent Smith’s revelation that this is the second Matrix. The first Matrix, Smith says, was perfect, but we humans decided we wanted to define ourselves through our misery, and so we couldn’t accept it. This is the technological version of the Garden of Eden story from Genesis. There we see that the very first use of technology was clothing, so it is significant that Neo is reborn completely naked.

Within that framework, The Matrix is also the story of the chosen one’s doubts, slow realizations, and final discovery that it is he, and not anyone else, who is the savior. Anderson must first be convinced that the realm he inhabits as Neo has provided him a glimpse of the true reality, while his everyday existence as Thomas Anderson is actually the false consciousness, the world of the Matrix in which he senses, but cannot prove, that something is terribly wrong. This thought tortures him like a “splinter in the mind.”

Neo is contacted first by Trinity, a slightly androgynous female counterpart to his slightly androgynous masculinity. It is she who leads Neo to Morpheus. Trinity is an obvious allusion to the biblical concept of a triune God consisting of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Because of the long-standing patriarchal metaphor for God, it is quite humorous when Neo says to Trinity, “I always thought you were a guy.” Also of note is the fact that the word “trinity” never actually appears in the Bible. It is during Neo’s second conversation with Morpheus, just after he wakes up from being interrogated, that Morpheus reveals his role as John the Baptist by saying, “You may have been looking for me for a few years, but I’ve been looking for you for my whole life.” However, Morpheus also plays the role of God the Father to Neo and the rest of the small band of rebels. He spends a significant part of the film teaching Neo the nature of “reality” as opposed to the world of the Matrix. When Morpheus is captured by the agents, as his body lies there helpless, Trinity says, “No, he’s much more important than that. He’s like a father to us.”

To join Morpheus and Trinity in experiencing the depth of this true reality, Neo must be born again. As he is jacked in to the initiation sequence, Cypher tells him, “Buckle your seatbelt, Dorothy, ’cause Kansas is going bye-bye.” Reeves’s character is literally born again into the new world in a visually explicit birth from a biotechnical womb that spits him out like a newborn infant: hairless, innocent, covered in muck, and eyes wide open in awe. He sees that he alone, of all the millions of entombed and enwombed humans plugged in as batteries to the Matrix’s mainframe, has been allowed to break free of his shell. The wombs are slightly opaque, allowing the inhabitants to at least glimpse a portion of the reality to which they are enslaved. The implication is that everyone can be freed, following the example set by the savior. (There is also a nice 2001 star child visual reference during this sequence.)

Just prior to his rebirth, Neo turns aside and sees a fragmented mirror, which becomes whole as he looks into it. He is about to make the journey into the self, or psyche, and the metaphor of a shattered universal mirror is one that Huxley and others have also used. He reaches out and touches the mirror, which then becomes whole, nicely referencing I Corinthians 13:12, “For now we see through a glass darkly, but then face to face.” The mirror then liquefies and swallows Neo, confirming for us that this is essentially an inward journey he is making. Upon being reborn, Neo asks Morpheus why his eyes hurt: “Because you’ve never used them,” comes the reply. Or, as William Blake puts it, “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” In one of the first scenes, we see Neo sell a software program to a character named Choi for two grand, while Choi comments, “You’re my savior, man, my own personal Jesus Christ.” Choi’s reference to mescaline in this conversation is a reference to Huxley’s mescaline experiment book, The Doors of Perception. Huxley’s title is drawn from the William Blake quote and was also subsequently the source for the name of Jim Morrison’s rock group, The Doors. In Greek mythology, Morpheus was the god of dreams, and his name is the linguistic root for words like “morphine” (a drug that induces sleep and freedom from pain) and “morphing” (using computer technology to seamlessly transform from one reality to another). This resonates with the ability of Fishburne’s character to morph back and forth between the dream world (the “real” world) and the waking world (the Matrix). Morpheus asks, “Have you ever had a dream, Neo, that you were so sure was real? What if you were unable to wake from that dream, Neo? How would you know the difference between the dream world and the real world?” The stage is now set for the film to equate the dream world with the digital world, the world of pure consciousness that exists in infinity. It is an equation that works, because life on the screen is a disembodied life, a virtual existence where the rules of society and the laws of physics don’t necessarily apply, which is why online relationships are so intoxicating and addictive. It’s also one reason why they fail so completely when the people actually meet. Like a movie version of a book, the real version of an online person’s self cannot help but disappoint, simply because the codes and conventions of space and time are so constrictive of the power of imagination.

As Morpheus tells it, The One has been prophesied, like Jesus of Nazareth, from time immemorial. The revealer of ultimate truth is the Oracle, played as a soul-food mama (cf. Meet Joe Black) with more of a sense of humor than seriousness, who nevertheless gives Neo the key insight into the nature of fate versus free will that is critical to the film’s final twist. That the Oracle is a woman is also a key ingredient in the film’s theology. The brothers Tank and Dozer have their biblical precedents in the apostles James and John, who were also brothers and called the “sons of thunder,” which makes sense since both a tank and a bulldozer are modern technological “thunder” makers. But The Matrix is not simply a Christian allegory; it is a complex parable that pulls strongly from Judaism and other traditions. In their initial discussion about The One, both Morpheus and Neo are in cramped quarters wearing what is clearly the garb of concentration camp victims; rough-textured wool and blue-striped bed linens. But because Jewish history has not yet given us a political Messiah, and perhaps because Jesus was himself Jewish, the Wachowski Brothers seem to be comfortable relying on Jesus’ story as a precedent for their own. When asked if E.T. wasn’t a retelling of the Christ story, Steven Spielberg said he “resented” the comparison because he was Jewish. So too might the Wachowski Brothers have inadvertently relied on the only well-known resurrection messiah story lying around.

And yet critics are saying the film is equally influenced by Zen Buddhism or Eastern mysticism. Many of the lines, and certainly the martial arts sequences, are certainly reflect an Eastern influence. But people often make the mistake of assuming that Judaism and Christianity are somehow exclusively “Western” religions. Both are situated geographically and historically in Israel, which is on the Asian continent. The holy city of these two religions is Jerusalem, which sits in the navel of the world, as the meeting point of East and West. In other words, Judaism and Christianity are religions that share and have been influenced by both East and West, and have influenced both Eastern and Western philosophies since time immemorial. Thus, if you think you’re seeing a lot of Alan Watts’s Supreme Identity in the film, you probably are. But Watts isn’t seeing something new by saying that East and West can be reconciled, he’s simply pointing out what was there all along.

The Judas character, named Cypher, is sympathetically played by New Jersey tough guy Joe Pantoliano. Like Judas before him at the Last Supper, Cypher accepts his fate as traitor over a meal. Like Judas, who shares a drink with Christ at the Last Supper, Cypher and Neo share a cup while Cypher expresses his doubts about the whole crusade with the line, “Why oh why didn’t I take the blue pill?” We see Neo part ways with Cypher by not finishing the drink, but instead handing the remainder over to Cypher. We know Cypher is up to no good when he breaks the convention of social hygiene by finishing Neo’s drink for him after Neo leaves. Cypher also wears a reptile-skin coat, which alludes to the biblical figure of Satan as serpent. It is Cypher’s doubts about Morpheus’s certainty that Neo is The One (note the clever anagram of Neo = One) that causes Cypher to betray the cause, because he’s not certain he’s fighting on the right side, or at least not on the winning side. There is a nice mealtime scene, reminiscent both of 2001 and Alien, in which Mouse waxes philosophic about the nature, essence, and ultimate reality of food, which serves to confirm the drudgery of everyday life for this ragtag team of revolutionaries. The food scene, and the discussion of the woman in the red dress, confirm the loneliness and difficulty of life on the Nebuchadnezzar. Like the faithful of any religion, our apostles are tempted by the Matrix’s illusions and are often led into daydreaming or fantasizing that ignorance really can be bliss. This confirms the Christian idea that the believer really is an alien in this world and is only a visitor, a transient resident, an alien on a temporary visa. As the anti-Christian filmmaker Luis Bunuel accurately puts it, “Properly speaking, there really is no place for the Christian in this world.” Neo’s new life is living proof of this maxim.

It is immensely significant that Cypher’s deal-making meal with the agents centers around steak. First, meat is the metaphor that cyberspace inhabitants use to describe the real world: meatspace is the term they use to describe the nonvirtual world, a metaphor that clearly shows their preference for the virtual realm. Cypher says that even though he knows the steak isn’t real, it sure tastes like it. The stupidity and superficiality of choosing blissful ignorance is revealed when Cypher says that when he is reintegrated into the Matrix he wants to be rich and “somebody important, like an actor.” It’s a line you could almost pass over if it wasn’t so clearly earmarked as the speech of the fool justifying his foolishness. But meat is also the metaphor that media theorist Marshall McLuhan used to describe the tricky distinction between a medium’s content and its form. As he put it, “the ‘content’ of a medium is like the juicy piece of meat that the burglar throws to distract the watchdog of the mind.” This line illuminates the fact that many people watching The Matrix are seeing only the “content” of the kung-fu scenes and the electronica soundtrack while missing the serious sermon going on all around them. But it also heightens the point that the story is making about the Matrix itself, which is designed, like Huxley’s “brave new world,” to oppress you not through totalitarian force, but through totalitarian pleasure. As Agent Smith says, “Isn’t it perfect? Billions of people, just living out their lives, oblivious.” “Steak” is also the password revealed for the Web site at the film’s closing credits, though there are nine passwords in total that reveal hidden messages on the Web site.

Because it’s a Hollywood picture, Jesus has to have a girlfriend (as he did in The Last Temptation of Christ), who is fantastically played by the little-known Carrie-Anne Moss. Her character, Trinity, is a mix of Mary Magdalene and the Holy Spirit, as evidenced by her earthly-yet-celestial relationship with The One. She follows him everywhere, and the Oracle has told her she would fall in love with him, and so it is she who represents eternal, infinite, unbounded love by giving Neo the kiss of Princess Charming at the end with the line, “You can’t be dead, because I love you.” This line may have had you fighting the gag reflex, but the point is that love is stronger than death, that God is manifested by a triune love relationship, and this was simply the best way to show the miraculous Christ-likeness of Neo. The power of her love to bring him back from the dead is also foreshadowed by her statement that she is the “commanding officer” on the ship, indicating her authority over him. Love is stronger than death, but the film could have shown this in a better way, even if only by developing their emotional relationship by an extra five lines each. Then again, if the Wachowskis are planning two sequels, it would make sense to have them kiss with about as much passion as Leia kisses Luke in Empire Strikes Back. This way we won’t be shocked to discover that they were actually brother and sister, or part of the same heavenly family, all along. But the important thing to remember is that Neo really is dead before this, having been riddled with bullets by the three agents. After receiving the kiss, he is resurrected in the Hollywood equivalent of three days, which is about three seconds.

Upon rising from the dead, Neo experiences the cosmic revelation of his identity, similar and yet dissimilar to Superman. Superman has an Achilles’ heel in the form of kryptonite and is also powerless to save his father from dying—despite all his other strengths. Neo’s realization, however, is that he has no weaknesses, no fatal flaws, that he is in fact an infinite being. Having had the doors of perception fully cleansed, Neo can now “see” things as they truly are—which is in binary code. He looks down the hallway and sees the three agents as a series of flowing digits, meaning that he alone is now able to bridge the gap between analog and digital realm, able to control the digital rather than be controlled by it. Like the previous messiah that Morpheus alluded to, he is now able to remake the Matrix as he sees fit. He is a bulletproof Christ, not dying for our sins and coming back, but dying for his unwillingness to believe in his own power, who comes back to life through the power of someone else’s belief, and who then asks us to join him in the fight against the Matrix. Like Jesus, he is the intermediary between our “bound” selves and our free selves. His is the example we are called on to follow in order to remake the Matrix with him.

A sympathetic understanding of Agent Smith is to assume that his hatred of humanity was programmed by the AI of the Matrix. This would indicate that the Matrix has learned what humankind failed to learn, which is how to manage AI technology successfully. But Agent Smith’s “revelation” speech is flawed: man is obviously a mammal. The fact is that no animal moves instinctively toward an equilibrium with its environment. Every animal is forced there by the competition of other life forms. Mankind is unique insofar as it has, alone among species, been able to vanquish its competition. Agent Smith may have been more accurate when he referred to man as a cancer. Just as cancer cells are human, so also human beings are mammals. And Agent Smith, the film makes clear, also wants to escape the Matrix. He has been infected by the “virus” of humanity and is desperate to know the Zion access codes, not so much to destroy the revolutionaries as to free himself.

At the film’s conclusion, the invitation is clear. The film stops where it starts, with us staring at a blinking cursor on the computer screen in Room 303. Neo is making a call to us, sitting out there in the audience, to join him in fighting the Matrix’s bondage. Like the final scene in Superman, Neo flies up and out of the screen as if to help us break free of our bondage, to suggest that he really is real, to suggest that we really can be free. One interpretation is that Neo is flying into us the way he flew into Agent Smith, to liberate us by destroying our preconceptions. In order to understand our preconceptions, our bondage, our slavery, all we need to know is one thing.

Experience

“I can visualize a time in the future when we will be to robots as dogs are to humans.” —Claude Shannon, The Mathematical Theory of Communication, 1949

What is The Matrix? Your senses of sight and sound will be placed on continuous red alert as they experience information overload on a scale almost unimaginable. The Matrix is Marshall McLuhan on accelerated FeedForward. Scene cuts are visual hyperlinks. Fight scenes are PlayStation incarnated. What is The Matrix? It’s the Technological Society come to its full fruition. It’s Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis for the twenty-first century, in which we don’t simply work for the machine (rather than the machine working for us), but we are created, given life, and used by the machine exclusively for the machine’s purposes. It’s a modern pastiche of Hollywood’s latest special effects combined with John Woo kung-fu and more bullets, explosions, and gothic horror than Batman-meets-Bruce-Lee under the aural assault of a cranked-up electronica. But don’t let the packaging fool you. Because far more than the eye-popping special effects and ear-shredding soundtrack, it is the ideas and the dialogue that dazzle in The Matrix.

In other words, the Wachowskis seem to have asked themselves this question: How do you speak seriously to a culture reduced to the format of comic books and video games? Answer: You tell them a story from the only oracle they’ll listen to, a movie, and you tell the story in the comic-book and video-game format that the culture has become so addicted to. In other words, The Matrix is a graduate thesis on consciousness in the sheep’s clothing of an action-adventure flick. Whether you’re illiterate or have a Ph.D., there’s something in the movie for you.

What the word “matrix” actually means, according to the dictionary, is 1. The womb. 2. Hence, that which gives form, origin, or foundation to something enclosed or embedded in it. 3. The intercellular substance of a tissue. 4. The earthy or stony substance in which an ore or other mineral is bedded. 5. The hollow in a slab to receive a monumental brass. 6. Math, The square array of symbols which, developed, yields a determinant. In The Matrix, we see that the filmmakers intend almost every one of these meanings, and then some. Put another way, to understand The Matrix, it helps to know a bit about the history and theories of communication. In the above quote by Claude Shannon, we see the main premise upon which The Matrix hinges. The Matrix is the robot, and we are the dogs acting as servants to our technological masters.

But technology and theology aren’t far apart in this world where the Cartesian split between mind and body is made manifest, tangible, and interchangeable. Like 2001, The Terminator, and RoboCop, The Matrix envisions a world where artificial intelligence is not only more appealing than flesh-and-bone reality, but more intelligent than the species that created it. In Morpheus’s analogy, the purpose of the Matrix is to turn humans into batteries (i.e., energy sources) for the machines to do their work. What is their work? To keep us humans enslaved by our own illusions, chief of which is that technology is not enslaving us, but actually liberating us.

Keanu Reeves plays Thomas Anderson by day and “Neo” the computer hacker by night. In his analog existence, Anderson works as a top-notch programmer at the Meta CorTechs software corporation, in the most depressing of Dilbert-like cubicles, until he is freed by a FedEx delivery of the latest Nokia cell phone. Product placement in this film works so well you actually want to own what they own, especially Fishburne’s ultra-cool wrapless sunglasses, the most talked-about item on the film’s Web site.

Morpheus tells him that the secret he is on to is one that won’t go away, like a splinter in the mind. It is this: he’s a slave. Reeves’s character is a slave to technology, and to free his mind he must choose between a red and a blue pill. By the film’s end, his identity is made clear when he tells his archenemy, Agent Smith, “My name is Neo” just before “killing” him in the subway. By choosing his digital identity, he rejects a lifetime of programming and shows that he now knows that “The Matrix cannot tell you who you are.” Now he can rapidly learn to override the physical limitations of five senses, the laws of physics, and other unpleasantries of analog existence while he is in the Matrix. The intimation is that we can all be The One simply by choosing to see. The almost universal understanding of the battle scenes at the end, where the most sensory overload takes place, is that they are simply what audiences demand in a movie these days. Initially, they appear to avoid answering the questions raised by the plot with any “deeper meaning.” The big shootout at the end seems more like a copout. But in fact it serves to open the audience’s mind to the deeper meaning in a profound way. The best way to question whether the path you are on is correct is to see where it leads. In a culture demanding ever faster, louder, more dazzling everything, the only way to call this into question is to give them more than they asked for. The Matrix is technological speed and volume dialed up to 11, screaming at the top of its lungs, asking if you want to go any faster.

The telephone serves as the connection point between the two worlds. Interestingly, it must be an analog line, and not a digital or cellular/wireless phone, that makes this connection. The telephone, according to Marshall McLuhan, is an extension of the human voice. Walter Ong points out that the voice is the only medium that cannot be frozen; words disappear as soon as they are spoken. No freezeframe is possible, which makes the voice the only organic, living medium in the history of the species. The voice’s isolation from all the other senses, as we experience it on the telephone, highlights the fact that touch is our most deprived sense. It was from this principle that McLuhan created the tagline “Reach Out and Touch Someone” for AT&T in 1979. Thus, the analog phone call, and the human voice it represents, are the only possible way to retrieve someone who is trapped in the Matrix. Orality and an oral culture are what’s needed to escape the Matrix. This is why Trinity’s kiss saves Neo from death. She speaks and touches with the same organ of orality, and the content of her speech is love, the power that drives all true communication. Neo’s final voice-over shows him telephoning the audience, asking them if they want to become real.

As the credits roll, one of the Web site’s nine passwords is revealed, and we can enter it to find out more. Entering your own email address gets you an e-mail from morpheus@whatisthematrix.com with the line, “The Matrix has you.” If you’re getting e-mail, it certainly does. Or does it?

Question

One of the perpetual pleasures of The Matrix lies in the fact that, unlike the majority of what Hollywood puts out, this film does not insult the viewer’s intelligence. Quite to the contrary, The Matrix has something to fill your cup whether your mental capacity is that of a thimble or a bucket. It is a pleasure that increases with time, because you see more and get more out of it with each viewing. Another recent film that rose to this level was The Game. In that film, the purpose of the Game was to discover the purpose of the Game. In The Matrix, the essential question remains even after the film is over: What is the Matrix? Executive producer Andrew Mason explains the intended audience effect best, perhaps, when he says that “The Matrix is really just a set of questions, a mechanism for prodding an ignorant or dulled mind into questioning as many things as possible.”

To prod us into the questioning mode, the movie presents as the basis for its plot a world almost completely incomprehensible to our minds. It is a world in which all reality is nothing but some electrical signals sent to our brains. It is one thing to have your ninth grade English teacher ask you “If a tree falls in a forest and there is no one around to hear it, does it make a sound?” It is something completely different to have to figure out that the Neo with the socket in the back of his head is the real Neo. We then make the journey with him to try and understand how to operate within a world that is purely in his mind. The beauty of the movie is that it takes us almost as long to figure this out as it takes Neo. If The Matrix has engaged our imagination, we spend over two hours with our minds wide open seeking answers to questions we might never have asked. Having survived the experience, we are now freed to question other parts of “reality” that always seemed beyond questioning.

Unlike any of the dozens of other films it pays homage to or appropriates through intertextual reference, The Matrix is doing something absolutely unique in the history of cinema. It is preaching a sermon to you from the only pulpit left. It is calling you to action, to change, to reform and modify your ways. Can a movie successfully do this? Or is a piece of cinematography, by the codes, conventions, and conditions of attendance that surround it, also and necessarily just another part of the Matrix? Jacques Ellul said that the purpose of one of his books (The Presence of the Kingdom) was to be “a call to the sleeper to awake.” I don’t know the answer to the question, and it probably ultimately hinges on the individual viewer’s pre-existing awareness, but if a film can wake us up, then this is it.

In The Matrix, technological progress is portrayed in its extremes. Some of the questions this should inspire us to ask are:

- Do we have technology or does it have us? The answer, which is neither absolute nor binding, is in the hands of the audience.

- What if we made computers that were so good that they were smarter than we are? This question has been posed before, but never in such a unique way. Instead of being destroyed by computers, we become their puppy dogs.

- What if reproductive technology were perfected to the point that sex and motherhood were no longer necessary? Even the “romance” in the movie is unerotic (Neo and Trinity are androgynous), as should be expected in a future where sex was unnecessary. What if people were bred simply for convenience (ours or the computer’s) in pods on farms?

- What if we progressed so far technologically that it destroyed us, and all that remained of our technology were the sewer systems? Although nuclear weapons are never mentioned in the movie, the charred remains of earth above the ground are a clear allusion to nuclear winter. Zion is in the core of the earth “where it is still warm.”

- What if communications technology progressed so far that information was delivered directly to the brain, bypassing the senses? What if someone other than ourselves were in control of the information flow? How different is this from television today?

“What is the Matrix?” is a question that never stops being asked because it is as old as humanity itself. We have always used technology to improve our condition in life, yet in the embrace of each technology we find the classic Faustian bargain, a gaining of one thing at the expense of another, often unseen thing. And it is the unseen thing that then comes to dominate our lives, enmeshing us in a network of technological solutions to technologically-induced problems, forbidding us to question the technology itself.

What is the Matrix? If you’ve read this far, you deserve an answer.

Answer

“Literacy remains even now the base and model of all programs of industrial mechanization; but, at the same time, locks the minds and senses of its users in the mechanical and fragmentary matrix that is so necessary to the maintenance of mechanized society.” (italics mine) —Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, 1964

“All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and still he’d see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across the colorless void . . .” (italics mine) —William Gibson, Neuromancer, 1984

If you’ve read everything leading up to this, you no doubt thought at some point that there really was no answer to the question. That just like the movie, all anyone could do was continue to find new ways to ask the question. Well, there is an answer, but it is not an easy answer. Like Neo learning to accept that his world was largely made up, the answer to “What is the Matrix?” is something that cuts to the core of your own reality. Like Neo, you should prepare to have your world turned inside out.

According to the protagonist’s guide, the Matrix is the “world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.” It is the construction the world has become to hide what we’ve known all along: we are slaves to a force much larger than our individual actions. It is the collective illusion of humanity sharing an artificial reality created by machines to keep them docile and helpless against their captors. But, in plain English, the Matrix is simply the Technological Society come to its full fruition.

In 1964, communications scholar Marshall McLuhan wrote his seminal book Understanding Media. At the time, McLuhan was called “the oracle” of the modern age by both Life and Newsweek magazines, and he has subsequently become the patron saint of Wired magazine and numerous communications departments across the country. His quote takes some unpacking and to understand McLuhan it helps to read his mentor Harold Innis’s Bias of Communication, his fan Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy, and his contemporary Jacques Ellul’s Technological Society. These books cast light on the question of “literacy as the base and model of all programs,” but also on the critical point that what McLuhan means by the term “matrix” is precisely what the Wachowski Brothers take it to mean: a system of control. Neo’s initiation into understanding the Matrix in the movie is a literal step into a fragmented mirror in which he discovers just how profound the control of modern society really is.

The Matrix arises at the point that the machine species realize that the human species is a virus that will destroy the ecological balance between the environment and itself if left unchecked. AI will destroy us once it perceives that we are a threat to its survival. But artificial intelligence doesn’t actually have to be smarter than we are in order to dominate our lives. We could simply continue to think, as we have for the last hundred-plus years, that technology is always the solution to any particular human problem. Thus, the Matrix, while ostensibly being future technology’s enslavement of the human race, in appearance actually resembles the industrialized world as we find it on the day we enter the theater. In other words, the Matrix is the trap the world has become. It is human hubris writ large. We all instinctively feel that technology, while giving us jobs and helping us balance our checkbooks, is nevertheless taking us somewhere we don’t want to go. But the trip is so fun, we keep trying to answer the question “Where do you want to go today?” as though the choice were ours.

In modern society, the electronic foundation of our culture has embedded each of us into a Matrix that affects us in unique and personal ways, and from which it seems nearly impossible to escape. Subcultures like the Amish or the Bruderhof Communities strike us as reactionary Luddites because, in escaping the Matrix, they have not transformed the culture as much as they seem to have ignored or bypassed it. And yet we should not be so quick to dismiss their examples for our own lives. They stopped watching television when they realized their children weren’t singing as much. They stopped using e-mail when they realized that it wasn’t improving communication, but rather had a destructive tendency. In a similar vein, Ted Kaczynski’s credibility ended where his package bombs began. While we will never condone murder, it has yet to be acknowledged by any of our public intellectuals that Kaczynski had some very valid points to make about the failures of the technological society in providing the human species with a meaningful and purposeful way of life. And it is arguable, though despicable if true, that his points would never have been heard had he not sent explosive messages, the equivalent of the SYSTEM FAILURE message that the Matrix ends with and which Adbusters magazine has used as a metaphor for the imminent collapse of our current cultural trajectory.

Consider two worlds: One where everyone is told what to think by a box that they watch for half their waking hours, and the other where everyone has that signal sent straight to their brain. In the first world, everyone is educated systematically to see the world a certain way, and those who dissent are eliminated from the educational hierarchy, all the while claiming that they have freedom of expression. In the other, everyone is educated systematically to see the world a certain way, and those who dissent are eliminated, period; all the while, reality is so radically different from this made-up world that most people would choose the imaginary if given the freedom to choose. In the first one, most people find purpose by seeking employment with large impersonal organizations that only see their usefulness in terms of the one thing they were hired for. In the second one, everyone’s purpose is employment by a large impersonal machine that only sees their usefulness in terms of one thing: the energy they can supply.

Recall the scene in which Thomas Anderson is reprimanded for being late to work. Recall that Trinity was famous for hacking the IRS database. Recall Agent Smith’s list of what was a “normal” life: “You work for a respectable corporation, you have a Social Security number, and you pay your taxes.” Sprinkled liberally throughout the movie are hints that the Matrix is really our present world. How better to control millions of people than to convince them that they are living a “normal” life in 1999? When Morpheus is giving Neo his long explanation of the Matrix, he says, “It is there when you watch TV. It is there when you go to work. It is there when you go to church. It is there when you pay your taxes.” These are all components of modern life that serve to control us and can easily be abused to the point of enslaving us.

The reasons we accept this control vary, from watching TV because we like entertainment to paying taxes because we feel we have no choice in the matter. The message of The Matrix is that we are already pawns in a modern technological society where life happens around us but is scarcely influenced by us. Whether it is by our choice or unwillingness to make a choice, our technology already controls us. In an attempt to wake us up, the movie asks us to question everything we believe about our present circumstances. Even if it feels good, is it good for us? Are those things that seem beyond our control really untouchable? If we do not want to wake up, then the answer is yes. However, for those with a splinter in the mind that will not go away, the challenge has been made to open your eyes and seek true reality, and ultimately to escape from the Matrix.

Want more on The Matrix? Order your copy of Taking the Red Pill.